“It’s wonderful to release it from my brain,” Bunce says over the phone 10 days before the Yukon premiere of Our Lady of the Home. “Because I’ve had it inside me for so long, it was getting claustrophobic.”

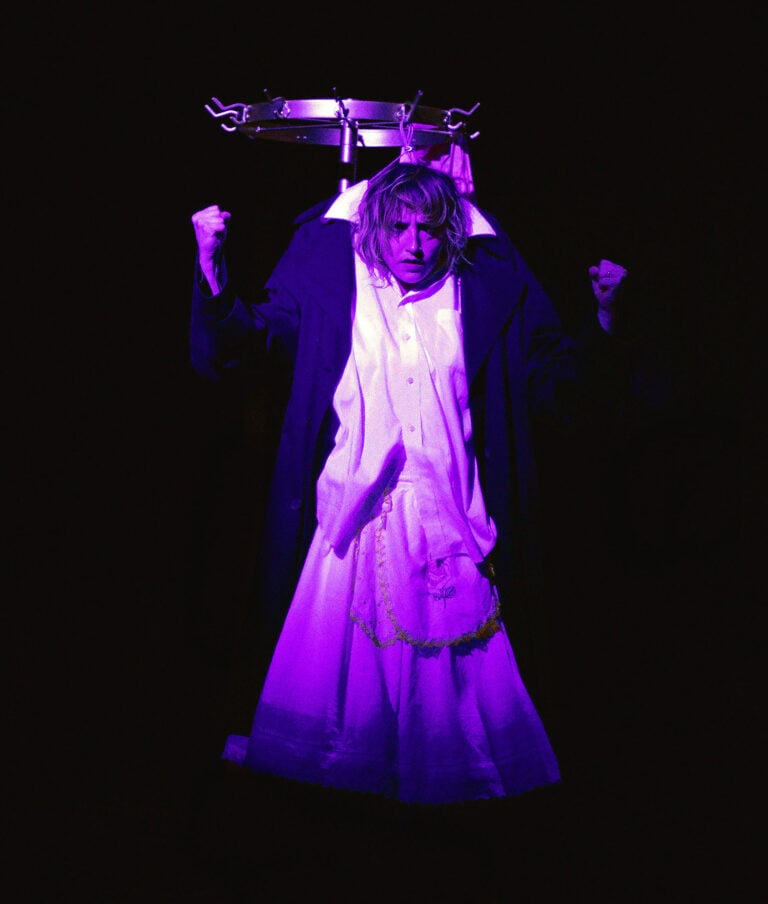

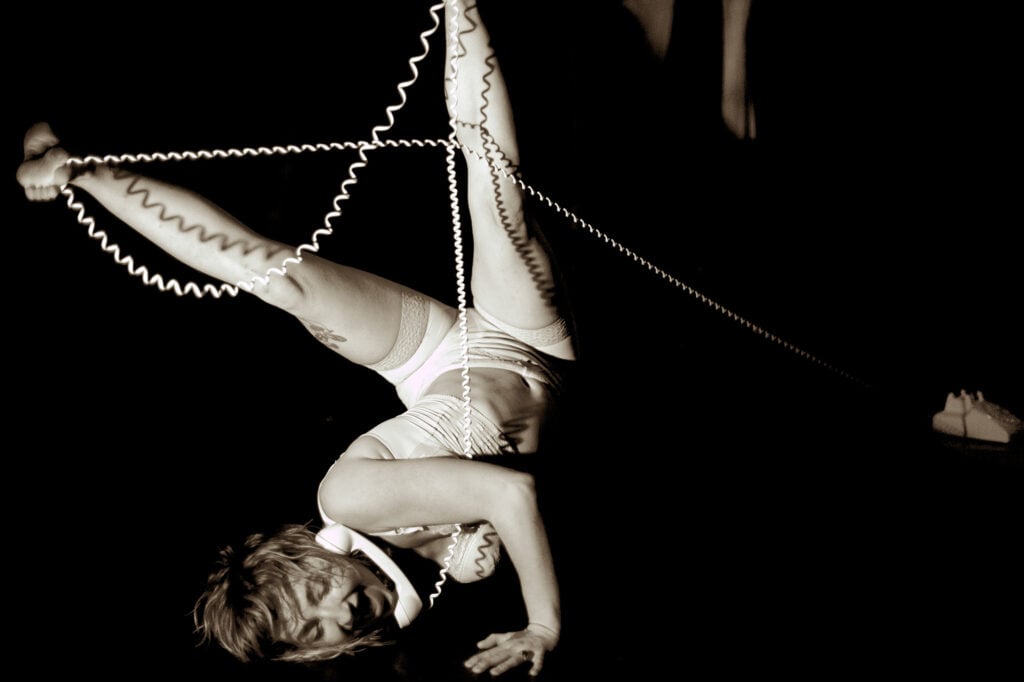

In a way, that feeling mirrors the show, which revolves around a 1960s housewife named Liza, trapped in her home one day. Over the course of the hour-long performance, Bunce, through Liza, explores questions around substance use, gender roles, authentic choice, empowerment when it comes to our own health, capitalism, mental wellness and more.

If that sounds like a lot, just imagine squeezing it all into five minutes. That’s how the show started when Bunce first developed it while attending the National Circus School in Montreal. After graduating in 2019, she expanded it into a 15-minute set, eventually securing funding in 2023 to blow it out into a full show.

Since beginning performances in July of 2025, she continues to refine the show as she learns more about her audiences and the character she created—even though the idea came from personal experience.

When Bunce first left the Yukon at 16 to attend circus school, doctors told her she had anxiety and depression. For five years, she took medication to manage that. It was helpful, she says, but she also thinks feeling depressed and anxious is a reasonable reaction to leaving home at 16 and moving to the other side of the country. The experience made her consider the context in which people are unwell, and how women, especially, feel the need to change something inside themselves to achieve wellness rather than looking at the external factors that may be making them sick.