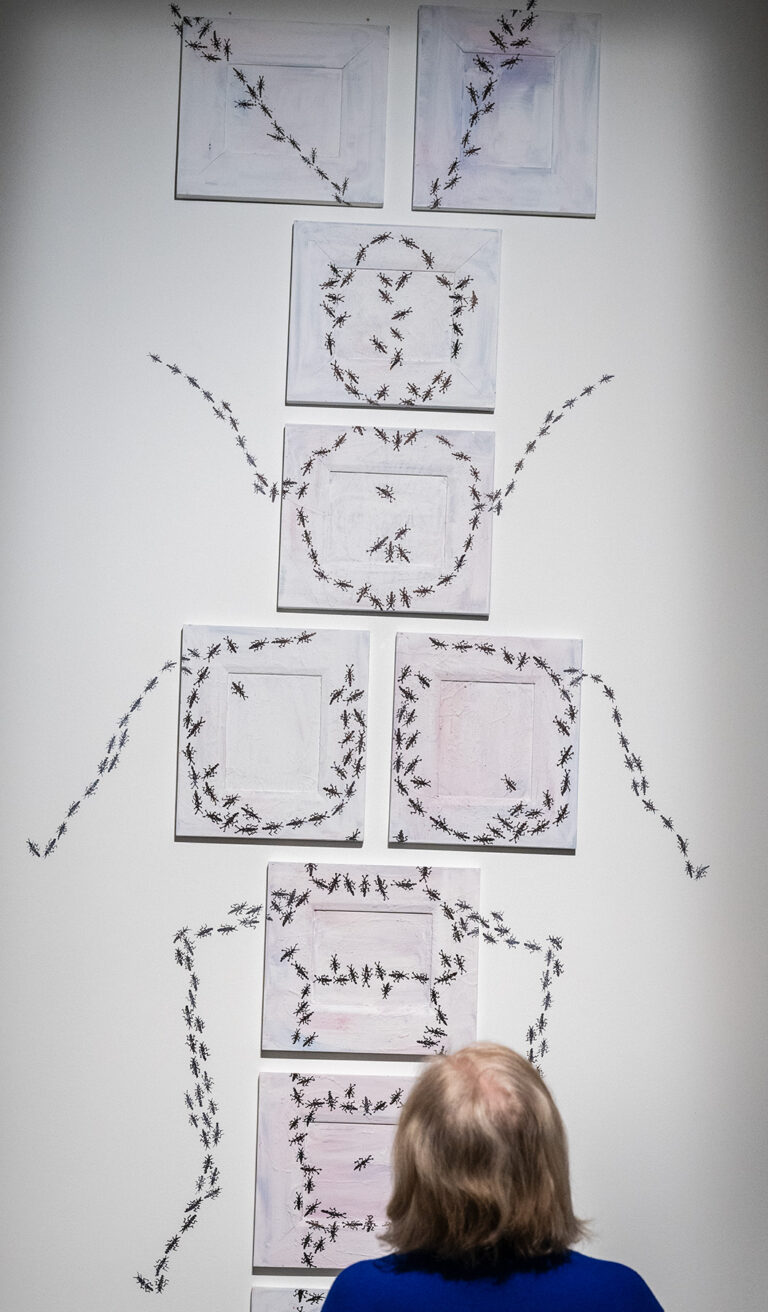

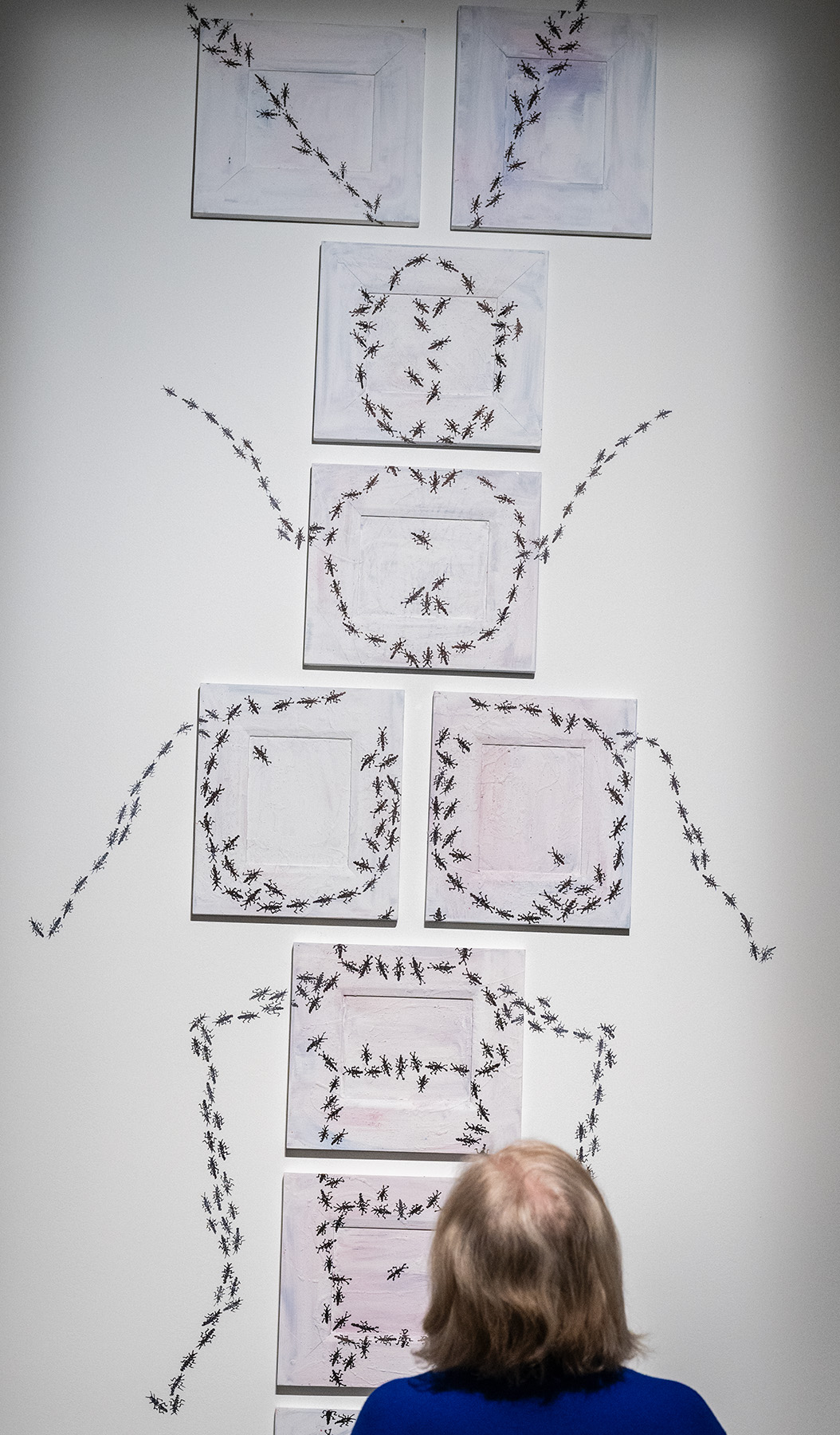

He initially brought sketches to Baker-Johnson, who then asked questions that led to Godin making 3D sculptures from plasticine for her reference. From there, Godin says he learned which elements could be realistically created versus what would have to be representational. For her part, Baker-Johnson (who kept one of Godin’s reference textbooks) learned to love the little bug.

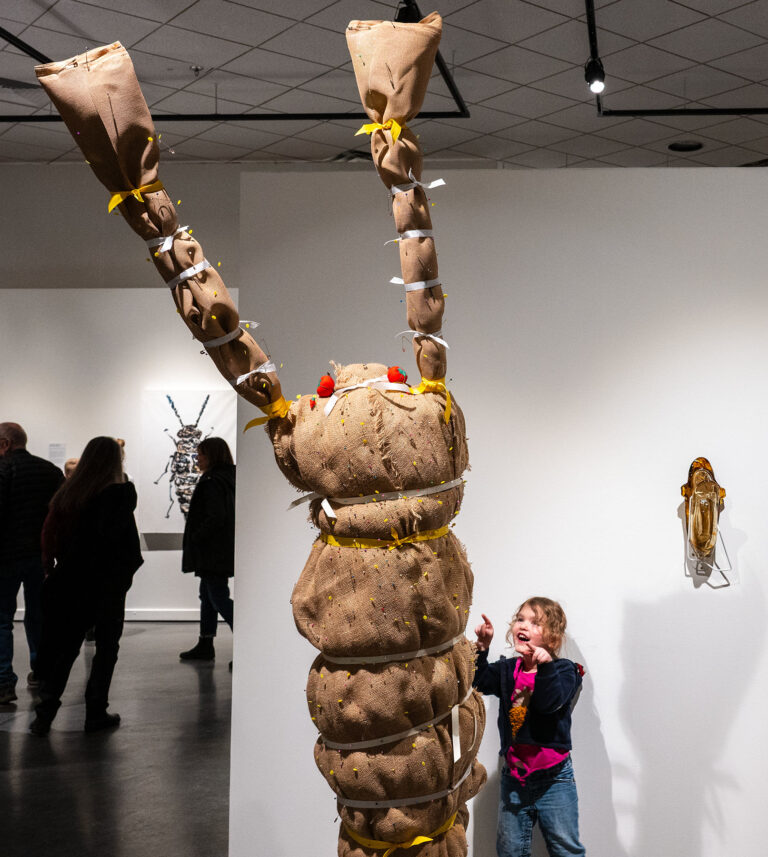

Godin hopes she’s not the only one. He says it was great to see the number of people who came out to the March 6 opening. Partly, this was because he wants viewers to appreciate the genitalia for their aesthetic qualities, but he also wants people to look at the world differently.

When he started doing rove beetle work, hardly anyone knew about the bugs, which prey on maggots and other insects, maintaining ecological balance in their habitats.

“There is life everywhere, all around [you], everywhere you are. There is so much to discover,” says Godin. “You don’t have a name for it, you don’t see it. Once you have names, then you can start appreciating them for what they are and the service that they provide to the forest.”

The exhibit is open Monday-Friday, 10am-5pm and during evening performances.