Atlantis Program Notes

A Note from co-creator Brian Fidler Atlantis started with the desire to create something ridiculous and entertaining with a group of fun, talented people. This summer I traveled to Japan and for the first week I was up at…

Tosca. A single word that evokes passion, politics, love, faith, and death. For those of us who care deeply about opera, this work by Giacomo Puccini, Luigi Illica, and Giuseppe Giacosa stands among the most visceral and immediate experiences our art form can deliver. It is an opera that feels alive from the first sharp chords of the orchestra through to its final, shocking leap.

When Puccini began work on Tosca, he was already an established name following the successes of Manon Lescaut and La bohème. This new story, based on Victorien Sardou’s play, was considered controversial—too violent, too political, too sensational. Yet Puccini saw in it the perfect subject for music: an opera set in real places, over the course of a single day, driven by human emotion at its most raw.

Those sharp chords at the beginning? They are Scarpia’s theme. His presence haunts the opera from the first bar. In Tosca, we are given no overture to gently guide us into a world. Instead, Puccini throws us immediately into revolution, danger, and desire.

Tosca herself is one of opera’s most complex heroines. She is an artist, a lover, a woman of faith, and ultimately a figure caught between passion and political violence. Within a single act, she moves from jealousy and tenderness to fear, manipulation, and sacrifice. Is she naïve? Fierce? Devout? Heroic? The truth is: she is all of these things.

And opposite her stands Scarpia. A man of immense power, outwardly devout yet inwardly corrupt, he embodies the abuse of authority. He manipulates Tosca by exploiting her faith, her love for Cavaradossi, and her very sense of self. He is both timeless and chillingly current.

Set in Rome, June 1800, the opera is rooted in real history: Napoleon’s advance, the collapse of monarchist forces, and the instability of power. Puccini weaves these political tremors into the fabric of intimate human relationships. Every aria, every duet, every confrontation is connected to the question of how individuals survive—and resist—when caught inside the machinery of power.

Audiences over the years have debated Tosca’s choices. Does she act out of desperation? Out of courage? Out of love? Today, we can view her as someone trapped in a system that affords her little agency, fighting to hold onto her integrity and dignity. Her final act is both an escape and a statement.

Tosca offers no easy answers. But it offers us Puccini’s music—sweeping, intimate, terrifying, and tender. It is music that pulls us directly into the heart of the drama, music that still resonates more than a century later.

Tonight, may you encounter Tosca with open eyes and ears, and may you find yourself moved, disturbed, and awakened by this story that continues to reflect our human struggles.

It has been incredible to partner with the Yukon Arts Centre. To be a part of bringing opera to the North over the last 7 years is awesome. This production of TOSCA builds on the past and boldly opens our eyes to dreaming of the future.

A big thanks to the National Arts Centre and to this building partnership between Edmonton Opera and the Yukon Arts Centre.

Joel Ivan, Artistic Director

I’m so proud to share this production of Tosca with you. It has been a long time since the Yukon has had opera on one of its stages, which makes this moment especially meaningful. Working with the Problematic Orchestra, the Yukon Community Choirs, some of the most exciting emerging vocal artists in Canada, and the brilliant creative team from the National Arts Centre has been an inspiring journey. I also want to thank the Yukon Arts Centre production team for their care and skill in bringing this beautiful design to life. Together, we have stretched ourselves, collaborated deeply, and pushed through the ceiling of what we thought was possible. This is what community building looks like, and I hope you feel the energy, dedication, and joy of everyone involved as you experience the performance tonight.

Casey Prescott, CEO Yukon Arts Centre

Program

TOSCA

Opera in concert

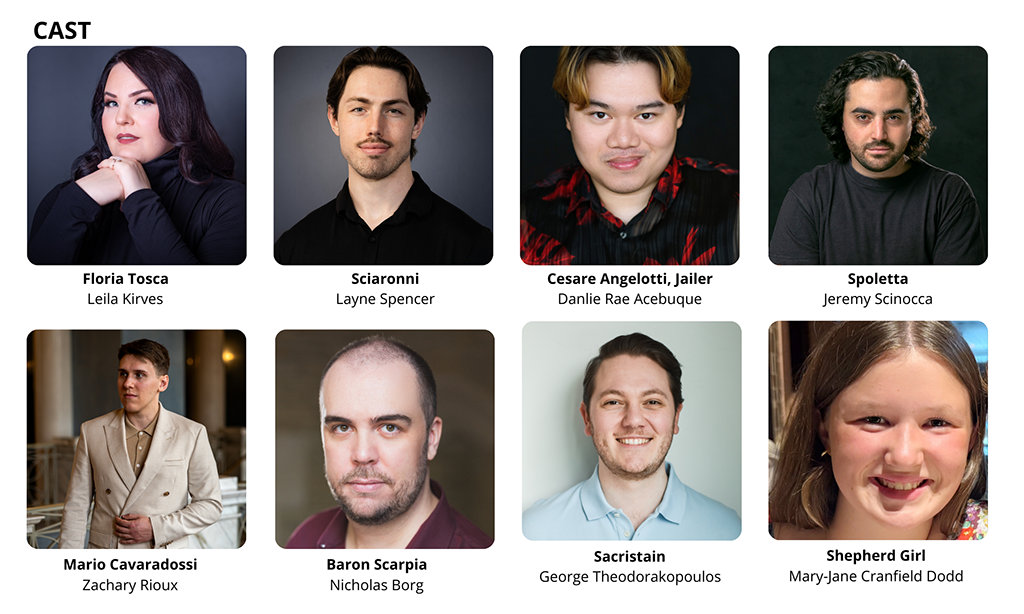

Produced in partnership with Edmonton Opera’s Emerging Artists Program

Music

Giacomo Puccini

Libretto

Giuseppe Giacosa, Luigi Illica

Performed in Italian with English and French surtitles

The performance is approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes, including one intermission.

ACT I (43 minutes)

INTERMISSION

ACT II (41 minutes)

ACT III (26 minutes)

A huge thank you to the individual Whitehorse donors: Paul Kishchuk of Vector Research, Joan Stanton, Bob Nishikawa, Al Cushing, Ron Veale and Duncan Sinclair.

ACT I

Rome, June 1800, the Church of Sant’ Andrea della Valle. Cesare Angelotti, escaped political prisoner, rushes into the church so he can take refuge in the family chapel of his sister, the Marchesa Attavanti. The artist Mario Cavaradossi, who was absent at his easel, returns to work on a painting—a portrait of Mary Magdalen; the church’s Sacristan scrutinizes it closely and says it resembles a lady who comes frequently to the church to worship. Cavaradossi, though, compares the face to the woman he loves, the famous singer Floria Tosca. After the Sacristan leaves, Angelotti emerges from the chapel and sees Mario, recognizing him as a political sympathizer. He tells the painter that he is being pursued by the Chief of Police, Baron Scarpia, and plans to flee disguised as a woman, using the clothes his sister left him. Hearing Tosca calling for him, Cavaradossi agrees to help his friend escape at nightfall and urges him to take a basket of food and go back into hiding. Tosca appears, jealously insisting to Cavaradossi that she heard him whispering to someone and the swish of skirts; she’s further roused by Cavaradossi’s portrait, which bears an uncanny likeness to the Marchesa Attavanti. He reassures her of his fidelity and promises to meet her that evening. After she departs, Cavaradossi lets Angelotti out of the chapel. A cannon shot is heard, announcing Angelotti’s escape. They hastily leave the church for Cavaradossi’s villa, where Angelotti will hide in an old well.

The Sacristan enters the chapel with news of Napoleon’s defeat; there is to be a Te Deum to celebrate the victory, and a cantata featuring Floria Tosca as soloist will be performed that evening at the Farnese Palace. The jubilant atmosphere is suddenly interrupted by Scarpia and his henchmen, Spoletta and Sciarrone, who search the premises for Angelotti. They find a fan bearing the Attavanti coat of arms and the empty food basket, which leads Scarpia to suspect Cavaradossi as Angelotti’s accomplice. When Tosca appears looking for Cavaradossi, she encounters Scarpia. He takes advantage of Tosca’s insecurities about Cavaradossi and the Marchesa by showing her the fan. Blind with jealousy, she storms out to confront Cavaradossi at his villa; Scarpia orders Spoletta to follow her. The Te Deum begins as Scarpia reflects on his diabolical plan to win Tosca for himself.

ACT II

That evening, at the Farnese palace. Scarpia sends a letter demanding Tosca to meet him in his chambers; he will make her yield to his desires. Spoletta arrives to inform his boss that Cavaradossi has been found and arrested, but Angelotti remains at large. The artist is brought in for questioning and denies knowledge of Angelotti’s escape. Tosca, alarmed by Scarpia’s note, rushes in and embraces Cavaradossi, who pleads for her silence. Cavaradossi is then taken into an adjoining room. Scarpia begins to interrogate Tosca as Cavaradossi is heard being tortured next door. He tells her she can save her lover if she discloses where Angelotti is hiding. She denies knowing anything until Cavaradossi’s agonizing screams eventually overcome her; confused and exhausted, she says, “The well…in the garden.”

Cavaradossi is brought out from the torture chamber; he asks Tosca if she divulged the location of his friend. Tosca reassures him she did not, but Scarpia commands Spoletta to go to the hiding place, revealing her betrayal. Breaking news arrives that Napoleon is victorious at Marengo; Cavaradossi exults, thus confirming his guilt and sealing his execution. As Mario is dragged away to prison, Scarpia invites Tosca to sit with him as he finishes eating his supper. He offers Tosca a deal: if she gives herself to him, her lover will go free. She vehemently rejects him in disgust. Spoletta returns, reporting Angelotti’s discovery and subsequent suicide. In desperation, Tosca finally consents to Scarpia’s terms for Cavaradossi’s freedom. Scarpia instructs Spoletta to arrange a mock execution, which must take place before Tosca and Cavaradossi can leave Rome. Tosca further negotiates safe conduct for her and Cavaradossi. When Scarpia finishes drafting the order and goes to embrace her, Tosca, who has taken the knife from the table, plunges it into his heart. She pries the order from the dead man’s fingers and steals out of the room.

ACT III

The following morning, the prison at the Castel Sant’Angelo. As dawn approaches, a shepherd is heard singing. Cavaradossi is received by the jailer, and in his final hour, asks for permission to write a farewell letter to Tosca. He loses himself in memories of her. Tosca is escorted to where she will find Cavaradossi. Seeing him, she rushes to him and shows him the order for safe conduct, explaining how she got it from Scarpia. She informs Cavaradossi of the necessity of going through the mock execution and that he must make it look as convincing as possible. The firing party arrives and carries out the execution. Cavaradossi falls; “how well he acts it!”, exclaims Tosca. But when she approaches his body, she discovers Scarpia’s final cruel trick on her: Cavaradossi is dead. Cries ring out—Scarpia’s murder has been discovered. As his men rush to apprehend the guilty Tosca, she climbs the parapet and leaps to her death.

Synopsis by Hannah Chan-Hartley, PhD

GIACOMO PUCCINI

Tosca

Since its premiere in Rome in January 1900, Puccini’s opera Tosca has captivated audiences all over the world. Based on Victorien Sardou’s 1887 play of the same name, this gripping drama tells of the love between the opera diva Floria Tosca and the painter Mario Cavaradossi living in the brutality of papal Rome during the throes of Napoleon Bonaparte’s revolutionary campaign in 1800. Despite frosty critical reception throughout its performance history, Tosca’s status in the repertory is firmly cemented, with its strong characters and compelling music a powerful showcase for some of opera’s greatest singers.

Puccini probably came across Sardou’s play—a vehicle for the celebrated French actress Sarah Bernhardt—not long after its 1887 premiere for he considered adapting it as an opera in 1889. However, it wasn’t until after he saw Bernhardt perform in an 1895 production in Florence that he finally decided to pursue the project. He enlisted Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica to create the libretto, following the success of their collaboration on La bohème, which premiered in 1896 to resounding acclaim. In 1898, Puccini showed the finished libretto to Sardou who heartily approved it. Two years later, Tosca premiered on January 14, and over the following year, it became an international sensation, with important performances at Milan’s La Scala (conducted by Arturo Toscanini), in Buenos Aires and London, and at New York’s Metropolitan Opera.

Although sticking closely to the plot of Sardou’s play, Puccini’s Tosca contains only traces of the political context foregrounded in the original, so to further intensify the emotional drama between the characters. Yet, as musicologist Michele Girardi has pointed out, the setting is crucial to the fates of Tosca and of Cavaradossi. The action takes place in Rome over 24 hours in mid-June 1800, around the time of the Battle of Marengo. (Napoleon’s victory at Marengo is announced near the end of the second act.) Each act is situated, respectively, in a church, a palace, and a prison—the principal institutions of papal Rome, whose repressive power and tyrannical authority are embodied in the characters of the police chief Baron Scarpia, his henchmen Spoletta and Sciarrione, and the Sacristan. On the other side representing the ideals of the French Revolution are the free-thinking, republican, religiously agnostic Cavaradossi and the political prisoner Cesare Angelotti; the devout Tosca is caught in between. As for Tosca and Cavaradossi, their love, as Girardi notes, is “a relief from the tensions of a difficult and oppressive life, like a breath of sensual happiness experienced somewhere far from the world, a refuge from the tentacles of papal Rome.”

Puccini underscores this fast-paced drama with imaginative music rich in tone colour and melodic inventiveness. Rome is evoked with authentic music from the liturgy, such as the Te Deum in the finale of the first act, and the sound of bells for the third act morning song sung by the shepherd, which uses a text in Romanesque dialect by the poet Gigi Zanazzo. The stage action is otherwise supported by an orchestral kaleidoscope of leitmotives, a compositional technique invented by Richard Wagner whereby each character, object, or idea is associated with a musical motive which recurs throughout the opera to complicate or deepen the plot’s arc. The three imposing chords on full orchestra that open Tosca is a motive of particular significance. Linked to the manipulative Scarpia (as confirmed with his entrance later in the first act), their complex harmonies also permeate the music like an unsettling unseen presence of his malevolence. Leitmotives are also used to reveal a character’s unspoken thoughts. For example, in the first act, the garden well in which Cavaradossi advises Angelotti to hide is complemented by an ascending motive of piquant chords. Listen out for its repeated return in the second act during Scarpia’s interrogation of Cavaradossi who refuses to reveal his friend’s whereabouts but is clearly thinking about it. Furthermore, motives reappear as the characters remember past events; the third act, notably, is full of musical reminiscences from the first two acts.

Amidst the progression of leitmotives, there are moments during which the action is suspended, and we gain further insight into the principal characters as they reflect upon their respective situations. In Scarpia’s monologue “Va, Tosca! Nel tuo cor s’annida Scarpia!” (Go Tosca! Now Scarpia digs a nest within your heart) at the end of the first act, he announces his aims to win the singer for himself, later revealing in the second act the way he will do it as he does with all women in “Ha più for te sapore la conquista violenta” (For myself the violent conquest has stronger relish). Tosca’s poignant aria “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore” (I have lived for art, I have lived for love), sung at the moment she faces the impossible situation of having to submit to Scarpia’s desires to save her lover, offers us another perspective of her character—one devoted to art, love, and religious observance, despite the intense jealousy and the emotional turbulence that we have thus far witnessed from her.

The third act is dominated by the melody of the opera’s most celebrated aria, Cavaradossi’s “E lucevan le stelle” (And the stars shone and the earth was perfumed), sung as he is flooded with memories of Tosca and their love in the final hour before his execution. While Tosca’s news that Scarpia has granted them safe conduct may have briefly alleviated his anguish over his impending fate, his sad response (indicated in the score) when she tells him he must go through with the mock execution suggests that he knows full well what will happen. He settles for listening to her voice as they dream of a future happiness that ultimately cannot be fulfilled in their reality, the tragedy of which is captured in the orchestra’s final thunderous statement of “E lucevan le stelle” at the opera’s conclusion.

Program note by Hannah Chan-Hartley, PhD

Joel Ivany

Stage Director

Judith Yan

Conductor

Jennifer Tung

Assistant Conductor

Vivien Illion

Assistant Director

Freddy Van Camp

Designer

Rebecca Klassen-Weibe

Repetiteur

Claire Thornton

Stage Manager

Kevin Waghorn

Company Manager

Artistic Director

Hannah Mazurek

Flute

Donna Reimchen

Clarinet

Erinn Komschlies

Laura Coatsworth

Bassoon

Stephanie Unverricht

French Horn

Martha Mason

Trumpet

Logan Bennett

Percussion

Kimberly Hart

Brian Gaas

Piano/Keyboard

Barry Kitchen

Violin

Katie Avery

Keiko Fujise

Jane Harms

Anna Billowits

Viola

Morgan Ostrander

Ben Barrett-Forrest

Cello

Pam Sinclair

Tim Sellars

Contrabass

Sarah Hancock

If you are interested in supporting the Problematic Orchestra, click here to make a donation.

Artistic Director – C.D. Saint

Marci Abrams

Laura Beattie

Zachary Bekk

Emma Devries

Travis Flath

Rachel Grantham

Louise Hardy

Catherine Hine

Daniel Korbela

Vincent Larochelle

Kyle MacDonald

Heather Milford

Kai Miller

Tory Russel

Kristina Schmidt

Ruth Stebbing

Angela Venasse

Jody Woodland

Karen Zaidan

Casey Prescott, CEO

Michele Emslie, Director of Programming

Josh Jansen, Director of Production

Mary Bradshaw, Director of Visual Arts

Martin Nishikawa, Technician

Adam Pope, Technician

Anika Kramer, Technician Intern

James Croken, Venue Coordinator

Nick Jeffrey, Box Office Coordinator

Mike Thomas, Marketing